October 2003

What is a Ceasefire and Why is it Important?

|

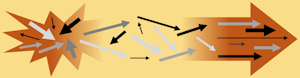

A ceasefire is a temporary cessation of violence that does not settle the larger conflict but is intended as a step in that direction. It is one of the first and necessary steps in a peace process aimed at transforming or settling a violent conflict. Its declaration alters the political landscape by providing a cooling-off period that paves the way for negotiation of issues that cannot be addressed during times of hostilities. Violence breeds anxiety, fear, and enmity that generally preclude negotiation and any hopes for a peaceful solution to underlying disputes. Instead, continued violence, with its associated bloodshed, encourages each side to pursue unilateral strategies that seek to destroy one's opponent outright or disable them as a viable force of social/organizational opposition.[1] To overcome the polarizing effects of violence, there may be a mutual or unilateral ceasefire declaration. However, unless there is strong political commitment and concerted leadership towards an envisioned peaceful end, such declarations are fragile and likely to breakdown in the first few months.[2]

Problems and Prospects

The ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict illustrates the frailty of such agreements. While the Israeli government maintains sole legitimate control of its use of force, radical segments of Israeli society have had a significant ability to aggravate the conflict even when the majority of the population, and the government's official policy, have sought a cease fire and negotiation with the Palestinians. For instance, a member of an extremist anti-Arab movement assassinated Yitzhak Rabin, a moderate Israeli leader who sought a peaceful resolution to the conflict in the mid-1990s, precisely because Rabin was willing to negotiate and perhaps make concessions to the Palestinians. Since then, the Israeli government has been led by hard-line and, arguably, antagonistic elements less-willing to negotiate with the Palestinian Authority. Similarly, there are multiple factions vying for power within Palestinian society, each with its own aims and interests. The Palestinian Authority has found controlling and incorporating the more radical groups, such as Hamas and the Islamic Jihad, extremely difficult. The result, especially when negotiations do not reflect the interests of extremist groups, seems to be waves of suicide bombings against Israeli citizens in an unambiguous attempt to disrupt the resumption of a ceasefire and peace process. Indeed, the most fanatical factions on both sides rely on conflict to justify their continuation as a social entity and, therefore, would rather prolong violence than relinquish their aims (often entailing the wholesale destruction of the other side). In turn, ceasefires between the two have been short-lived, as violence erupts and increasingly polarizes the two societies.

|

Mari Fitzduff talks about her experiences in Northern Ireland and covers everything from peacebuilding to paramilitaries. |

Any ceasefire can be tenuous because tensions and skepticism remain high. If one side lacks the sincere intention of pursuing a negotiated settlement, the whole process is jeopardized. Moreover, ceasefires are often manipulated as tools for political or strategic advantage. For instance, one side may use a ceasefire to reconstitute its war-fighting capacity and/or maneuver its forces into stronger tactical positions. One side may also undertake other provocative actions that are not in-line with the spirit of the ceasefire in an effort to weaken the position of its opponent, perhaps inciting the other side to break the ceasefire, bringing condemnation and pressures from third parties.

Thus, a successful ceasefire often requires a baseline of trust among adversaries. This takes the form of a psychological transformation, such as the realization that continued violence is self-destructive, the recognition of one's own role in the creation of the conflict or empathy for one's enemy.[3] However, the most difficult aspect of managing a ceasefire is the ability to gain the support of all stakeholders to a conflict or at least to ensure that actions taken by those with a minority view to disrupt negotiations do not lead to a breakdown of the ceasefire.

|

Mari Fitzduff suggests that cease fire agreements and peace processes take a long time to develop. |

Once enacted, ceasefires do have their own momentum. Civilian hopes of a peaceful resolution to an on-going conflict become inflated within warring societies, driving up the political costs of breaking the ceasefire. Moreover, ceasefires shift domestic political coalitions and generate new institutional interests in maintaining peaceful relations, even if simultaneous interests and coalitions opposing the ceasefire are generated. Pressure from third parties able to reward or sanction parties to an agreement can provide added assurances of and further highlight parties' interests in maintaining a truce. Indeed, ceasefires have increasingly been accompanied by the introduction of peacekeepers who monitor the agreements and provide a buffer zone between adversaries that helps alleviate anxieties and the potential for renewed violence. Indeed, the introduction of third parties is often a requisite for a ceasefire. For instance, Liberian president, Charles Taylor, in a ceasefire agreement signed with rebel forces, agreed to leave office if international peacekeepers (specifically troops from the United States) arrived to oversee the agreement and help maintain stability. Once third parties are introduced into a peace process, they have an interest in seeing it through and, therefore, provide additional resources and momentum to ceasefire agendas.

Conclusion

Ceasefires are inherently unstable. They are only implemented after hostilities have generated a great deal of enmity and distrust. Once a conflict has widened to incorporate numerous parties, the parties inevitably have differing interests. Some (who Guy and Heidi Burgess call "conflict profiteers") benefit from the conflict itself and hence seek to prolong it.[4] Other "hardliners" may seek escalation of the conflict and even aim for the total destruction of the opponent. Ensuring that these factions abide by or have minimal impact on ceasefire agreements is a difficult task for any governing body, particularly one attempting to gain acquiescence to proposed agreements while hostilities are still underway. Third parties can be valuable in helping to highlight the benefits of ceasefire agreements and assuage fears that bolster the arguments of ceasefire opponents. However, instituting ceasefire agreements also has dangers: they may be manipulated by one or all sides in a conflict; freeze, and thus legitimize, power and resource inequities between adversaries and within their respective constituencies; and, by allowing time for warring parties to reconstitute their forces, possibly set the stage for a more destructive conflict in the future.

[1] For non-negotiated paths to conflict settlement, see Louis Kreisberg, Constructive Conflicts: From Escalation to Resolution, 2nd Edition (Boulder: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2003), pp. 275-277.

[2] John Darby and Roger Mac Ginty, "Conclusion: Peace Processes, Present and Future," in John Darby and Roger Mac Ginty (eds.), Contemporary Peacemaking: Conflict, Violence and Peace Processes ( London: Palgrave Macmillan, Ltd., 2003), p. 265.

[3] Kreisberg, pp. 191-94.

[4] "Conflict Profiteers" essay in the Intractable Conflict Knowledge Base.

Use the following to cite this article:

Smith, M. Shane. "Ceasefire." Beyond Intractability. Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: October 2003 <http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/cease-fire>.